Between 1861 and 1865, Richmond, Virginia served as the capital of the Confederacy during its rebellion to preserve the institution of slavery.

The city no longer looks like it did then; gone are the iron foundries that armed Confederate soldiers, the offices that administered Confederate bureaucracy, the slave market in which families were forcibly separated, commodified, and shipped away. Yet in the last 155 years, remnants of Richmond’s history as the heart of the fight to preserve slavery have remained in plain sight.

Looming over downtown Richmond are the petrified forms of five white supremacists, the oldest, which commemorates Robert E. Lee, dating back to 1890. In the early days of June 2020, amidst worldwide protests against racism and police violence, protestors gave Lee a makeover. Adorning the base were cries for justice: “Black Lives Matter,” “No More White Supremacy,” “How Much More Blood?” “Hold Police Accountable.” In a matter of days, Richmond’s Robert E. Lee statue was transformed into a canvas of U.S. history.

In its graffitied glory, the statue now tells us more about U.S. history than it ever could before.

The controversy is nothing new. Since at least 2016, activists have purposefully tagged Confederate monuments with “Black Lives Matter” and other racial and social justice slogans. No sooner than three summers ago, a far-right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia that ended in the death of a peaceful counter-protestor pressured the city’s council to shroud the city’s statue of Robert E. Lee in black cloth.

Two years before that, when white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, the city of New Orleans vowed to remove four of its Confederate memorials as nationwide controversy erupted over the use and preservation of the Confederate flag.

Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and other Confederates have not been the only targets of controversy in recent months. On June 10, 2020, members of the American Indian Movement, like others before them, brought down St. Paul’s Christopher Columbus statue with ropes and cheers. Days earlier and thousands of miles away, UK protestors targeted a statue of slave trader Edward Colston and plunged his figure into Bristol Harbour. The list of removals (and resistance to such changes) continues to grow – and quickly.

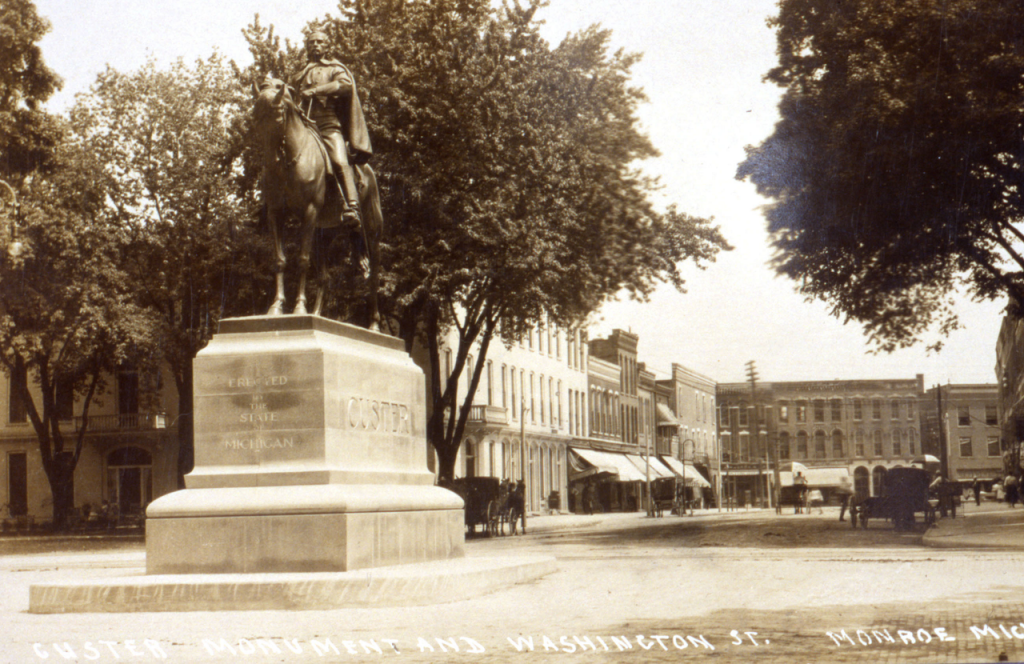

These controversies exist all over the United States. And they often appear in unlikely places: the Confederate Memorial Fountain in Helena, Montana (which didn’t even become a state until 1889). A statue of infamous “Indian Killer” George Armstrong Custer in Monroe, Michigan (Custer was from Ohio). And every commemoration of Christopher Columbus (who never even set foot on the North American continent).

The controversy is not a symptom of this moment. Sixty years ago, student activists at UNC Chapel Hill began a long legacy of organization in opposition to the campus’ Silent Sam statue, a memorial that went up with the purpose of honoring the Confederate troops who “sav[ed] the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South.”

Whenever statues and their destruction provoke debate, a familiar refrain echoes across social media, among communities and over the dinner table: why are these statues being removed? This question is often followed by another more pointed critique at removal itself: doesn’t this erase history? Rarely do such questions come with a more essential one: why were they put up in the first place? The answer, in fact, shines a light on the manipulation of history in favor of the few.

Confederate monuments are a popular example. The vast majority of Confederate monuments were erected long after 1865, many having been put up in periods of intense racial conflict. Data collected by the Southern Poverty Law Center shows significant spikes in construction during the Jim Crow Era as well as during the Civil Rights Movement. This isn’t mere coincidence. The United Daughters of the Confederacy, founded in 1894, orchestrated a propaganda campaign across southern states to uphold the Lost Cause myth — the idea that Confederate veterans ought to be honored for preserving a mythologized conception of southern benevolence, culture and heritage. The result has been public spaces that intimidate rather than include, as those who (literally) fought to preserve white supremacy are (literally) preserved.

“African American communities,” Michael Dickinson explains, “do not have the luxury of having idealized views of the past or the present.”

Close cousins to Confederates are statues that commemorate colonialism. Memorials of Christopher Columbus have long met resistance from Indigenous activists who condemn such commemorations as “public monument[s] to conquest.”

A recently dismantled statue to Spanish conquistador, Juan de Onate, served the same purpose, whose presence in Alcalde, New Mexico “was an act of violence upon Pueblo people.” Los Angeles’ Junipero Serra statue has since met a similar fate, fueling a generations-old conflict between the Roman Catholic Church and California Indigenous communities over the violence of Serra’s mission system.

Statues do not speak to us; they cannot tell us the complexities of historical actors, events, and processes. Nor do statues themselves make history.

Other statues lead more complicated, contested lives (and deaths). Take the statue of Ulysses S. Grant in San Francisco, toppled by protestors on June 19. The condemnation was palpable: how could protesters target the man who quashed the Confederacy? This question conveniently left out another aspect of Grant’s legacy: his administration, among other damages inflicted upon Indigenous nations living within and beyond U.S. borders, authorized the violent invasion and seizure of Lakota lands. Decades later, that land was desecrated in order to commemorate other U.S. leaders complicit in colonization — Mount Rushmore.

Statues do not speak to us; they cannot tell us the complexities of historical actors and events. Nor do statues themselves make history. On the contrary, statues to white supremacists, colonizers and other architects of oppression “erase” more history than they explain or create. Pro-Confederate groups trying to preserve the myth of the Lost Cause and fabricate a Confederate “heritage” sought to do so in metal and stone. Likewise, hundreds of statues of Christopher Columbus went up four and five hundred years after his “discovery” of a land he never set foot on.

Ultimately, statues and memorials commemorate, often with little nuance. Only with proper contextualization can memorials teach us something. Understanding the circumstances and causes behind them allow us to better understand the purpose they serve. Nearly without fail, these reflections reveal infinitely more difficult histories that statues conveniently replace.

History is an exercise in understanding change over time. It is also a constant debate, revision and reconceptualization of the past. The destruction and removal of statues is an opportunity to learn from history. We shouldn’t grieve it. We should embrace it. It is history in action. It is long overdue justice in action.

It is not surprising that the removal of memorials to slaveholders, traders and conquerors coincides with this moment.

As statues continue to fall and face whatever fates await them, the controversy continues to change and challenge. In turn, we are given a critical opportunity to learn. If this is what it takes for us to seriously confront the pains of American history, may the facades of the famous and the infamous be righteous casualties.

History, after all, is never set in stone.

TAKE ACTION: Follow and support the work of independent scholars, artists and activists at Monument Lab who aim to re-imagine the purpose and place of monuments.