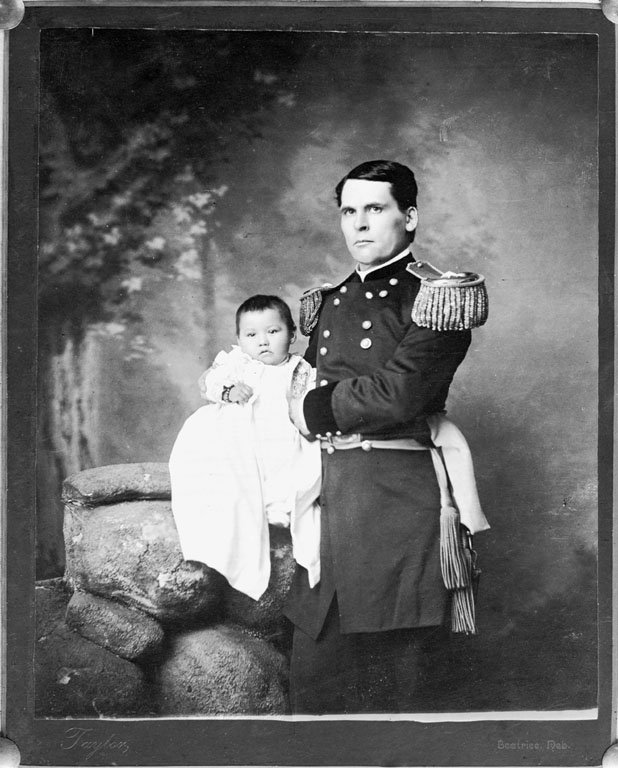

Zintkala Nuni was four months old when U.S. soldiers killed her mother at Wounded Knee in the winter of 1890. After surviving for multiple days buried under the snow while still tied to her mother’s back, Zintkala was found alive and returned to the care of fellow Lakota community members.

That was, until, a U.S. general removed Zintkala from Lakota custody, discarded her Lakota name for an Anglicized one, sent her to various boarding schools, abused her, and eventually left her at a mother’s reformatory. At 29 years old, Zintkala died from the Spanish Flu, which struck Indigenous communities from central New Mexico to Alaska’s westernmost edge.

Zintkala endured two pandemics. One was disease. The other was the colonial conditions that shaped her life from its very beginning.

A survivor of one of the most infamous massacres in American history, Zintkala was removed from her community and thrust into another that sought to strip her of her Lakota identity. An abusive household, parental negligence, forced attendance at violent institutions, and other stresses that began with her removal from Wounded Knee culminated in circumstances of poverty and poor health that rendered Zintkala particularly susceptible to influenza.

Yet even if Zintkala had remained with her Lakota community, her chances of surviving the pandemic may have been equally bleak; Oglala Lakota residents on the Pine Ridge Reservation were three times more likely to die from the Spanish Flu.

The myth that disease almost single handedly depopulated this continent in the wake of European invasions is an old one. Theories of “virgin soil” epidemics oversimplified Indigenous population loss to a matter of “biological difference,” rendering European culpability as only marginally significant. Yet recent work has bucked this belief once and for all.

Today, we cannot talk about the impact of disease on Indigenous peoples without also talking about colonialism.

The shift could not be more timely as another pandemic descends upon the continent, and, yet again, disproportionately threatens Indigenous peoples. The spread of COVID-19 across North America has exposed how colonialism places Indigenous peoples at greater risk.

Indigenous nations and communities have experienced this for generations. The pandemic has revealed the enduring structure of American colonialism — and an equally long history of Indigenous resistance.

Today, we cannot talk about the impact of disease on Indigenous peoples without aslo talking about colonialism.

Indigenous peoples living on reservations are at a disproportionately higher risk. Take the Navajo Nation, where over a third of the 173,000 residents living in an area the size of West Virginia don’t have access to running water. The Navajo Nation is not alone; of the 574 federally recognized tribes, only 40 have achieved water rights settlements expanding access to essential water resources.

Couple the critical lack of water with massive health disparities, an issue made worse by the federal government’s inability to fulfill treaty obligations. On average, federal funding toward health care tops out at over $11,000 per person; the Indian Health Service spends barely a quarter of that on those who receive its services. Where and when Indigenous people do receive critical healthcare, they may face health-jeopardizing discrimination, like the Native mothers at an Albuquerque hospital who were put on lists and separated from their newborns.

The disparities are no coincidence.

Inequities across Indian Country go hand-in-hand with rampant electoral disenfranchisement and voter suppression. The lack of political representation directly impacts funding, a major reason why the 2020 census remains a priority of paramount importance for tribal officials and leaders. But Indigenous communities hit hard by the effects of COVID-19 now face the possibility of an undercount of Native populations in the census.

Data that is either insufficient or distorted has prevented Native communities from protecting their members against COVID-19-related risks. When the Treasury Department began disbursing CARES Act funds, several communities received inadequate funding for business support, employment, public health resources and more.

The inconsistent disbursement of CARES Act funds already not enough came only after months of effort, largely on behalf of tribal governments and advocates, to receive any funding at all. As of mid-June, nearly two months after the Treasury’s deadline to disburse funds, some Native communities were still waiting to receive funds guaranteed in Indian Country’s $8 billion package.

Federal irresponsibility, a general lack of public health infrastructure, insufficient medical resources and other systemic issues shape and are shaped by tribal sovereignty — and how non-Native officials often fail to recognize it.

At least dozens of Native communities have closed tribal businesses and borders in an effort to keep COVID-19 out. In South Dakota, Governor Kristi Noem has pitched an unfounded legal battle against the sovereign Cheyenne River Sioux and Oglala Sioux tribes after both nations closed their borders.

A lack of understanding or regard for the sovereign status of Native nations has compounded efforts to contain the spread and allocate resources. Officials at the Center for Disease Control denied requests from tribal epidemiologists for essential COVID-19 data, citing ambiguity of tribes’ legal standing.

Consider, too, the social suffocation of American colonialism. As Washington’ DC’s football franchise only recently decided to hear decades-old calls from Indigenous advocates for removing racist mascots, others — like the Chicago Blackhawks—remain resistant to change. And on July 3, President Trump disregarded opposition from Lakota leaders to host an Independence Day rally on unceded Lakota lands in the Black Hills. Attempting to block Trump’s unauthorized entry to the Black Hills, at least twenty protesters were arrested and jailed.

Under the conditions of colonization and COVID-19, Indigenous histories face a dual threat. As Sappony reporter Nick Martin writes, elders “are people who fought on the frontlines to withstand American assimilation. They fostered our languages and our traditions. They carry with them stories and memories that will fade when they pass, precious fragments of their tribe’s collective story. But more than being living carriers of cultural knowledge, they’re our parents, our grandparents, aunties, and uncles.”

Community elders often possess knowledge crucial to preserving Indigenous pasts and futures. In an effort to protect elders disproportionately vulnerable to COVID-19, Protect Native Elders, has distributed over $300,000 of PPE and other essentials to over 60 communities.

Yet parts of Indian Country are now seeing long-fought battles finally materialize in victory. In early July, Lumbee and allied activists in North Carolina killed Duke and Dominion’s Atlantic Coast Pipeline project, a conflict ongoing since 2014.

That decision coincided with a court order requiring the Dakota Access Pipeline be shut down and its oil removed within 30 days. The Standing Rock, Cheyenne River Sioux, and Meskwaki tribes have opposed construction since the project’s inception in 2014. Opposition culminated at Standing Rock in the late summer of 2016, where thousands of Indigenous and allied water protectors faced state sanctioned violence to defend essential water resources and tribal lands. And a long-awaited SCOTUS ruling recently upheld Creek treaty rights as the “supreme law of the land”, affirming that a large swath of eastern Oklahoma remains Creek land.

The myth of Native passivity in the face of pandemic disease crumbles under scrutiny. Like past chapters in Native American history, the present pandemic has coincided with sustained, aggressive assaults on Indigenous autonomy and livelihoods, as well as efforts to silence Indigenous voices.

And yet Native nations refuse to allow such sufferings to shape their fates. Like generations before them who also endured the often fatal combination of colonization and disease, these nations continue to assert their persistence — past, present, and future.

Take Action:

- Use the National Indian Health Board’s Advocacy Tools to write to congressional representatives demanding prompt and proper dispersal of funding and support for Native nations.

- Keep up with the latest updates on Indigenous responses to COVID-19 with Indian Country Today’s COVID-19 Syllabus.

- Learn more about the history of how colonialism and disease have impacted Indigenous peoples in the past by reading essays from Beyond Germs: Native Depopulation in North America.